Today is Election Day in the US, and after the “shoot-self-in-the-other-foot” results came out this time last year, I decided the news – which for me was mostly podcasts – didn’t deserve my attention anymore.

I’ve always been a news junkie – from being an early user of Pointcast to listening to podcasts before they were even called that (I downloaded MP3s to a clunky Windows CE phone).

For well over a decade, my habit was a daily soundtrack of quality podcasts, and along with mostly getting through the The Economist audio edition each week. I was super plugged in – probably too plugged in.

However, somewhere I’d heard that the average book contains something like 100x more effort per word or per hour than a blog post or podcast episode. It made sense – the writing and re-writing of a manuscript, the editors, the fact-checking, the publishing, printing, marketing – there’s just a lot more work there. While the output isn’t guaranteed to be high quality, it’s clear that writing a book requires a lot more effort to create, and involves risk to their reputation by publishing it, than a podcast or a blog post.

So I decided to change the inputs. I stopped listening to pundits and started listening to authors – same hours, but with a very different signal-to-noise ratio. Over the next twelve months, those hours added up to seventy-five books – with the added benefit of a lot more insight and a lot less outrage.

Of course, “reading” is being a bit generous. With my Audible subscription, I listened, with all of those hours of a day when your hands and eyes are occupied but your brain is empty. With a busy house, that meant listening to books while cooking, doing laundry, working out or driving to the mountains. I know it’s not the same as quiet, contemplative reading – but perfect is the enemy of done, and this experience turned out to be surprisingly great.

This meant I turned my idle time into learning time. Some books I finished in a couple of days; others were a lot longer (hello, Steve Jobs at over 25h). So while it wasn’t ideal – and there’s a couple of interactive books on this list I haven’t finished – being a slightly distracted reader is a lot better than an aspiring reader full of (reasonable) excuses.

A few friends I’ve talked to about this lately have asked for recommendations and a list. I’ll share those below, and in the future I’ll have more details to share about why I loved the books I gave 5 stars to. But overall, I’d had a few reflections beyond the obvious that this has been 1000x better than listening to podcasts.

- History is underrated. Every generation thinks it’s the apex of progress – and as a creature of the tech industry, I’m probably more susceptible than most to that hubris. Reading history has been educational and grounding; biographies show how our ancestors wrestled with the same greed, courage, and confusion we do – just with worse lighting.

- Psychology is endlessly fascinating. We all see the world through the eyes we have, filtered by the experiences we’ve had and moderated by our feelings. Given this is unavoidable, one of the most powerful things we can do is understand ourselves better – more honestly, more clearly. This isn’t about self-help or self-change or self-healing – this is about trying to get to the truth, knowing that all of us are biological filters.

- Successful people are all weird – thankfully. This is great news for all of us who don’t try and “fit in” with a crowd. Sure, they’re often talented and they’re always hard working, but they’re also independent thinkers who are comfortable enough in themselves to never stop being curious and learning. Since you’re almost certain to be as weird to be reading my post as I am for writing this, I think that is pretty awesome.

- Making time for reflection is the next challenge. While my pace will probably slow now that TeamScore is rocking and rolling, I’m going to keep this “books over podcasts” habit going. However, the challenge I’m still a long way from solving is making the time to reflect, internalize and truly learn from the lessons on these pages (or through these earbuds).

Anyway, onto the list!

American Kingpin: The Epic Hunt for the Criminal Mastermind Behind the Silk Road

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Nick Bilton (2017). The story of the hunt for Ross Ulbricht, the creator of the “Silk Road” dark web marketplace for illegal drugs and services.

Review: A truly remarkable piece of journalism into a wild story, the journey of Russ Ulbricht from brilliant and frustrated libertarian to digital gangster is incredible. The fact this guy was recently pardoned for his crimes while “the good guys” at the FBI and the grieving parents in Perth continue to suffer is a travesty. An incredible tale by Bilton – he must be as mad as any honest person for how things have played out.

Billion Dollar Whale

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Bradley Hope, Tom Wright (2018). Exposes the story of Jho Low and the 1MDB scandal, a massive international fraud scheme that siphoned billions from a Malaysian state fund.

Review: Incredible story of absurd extravagance and brazen criminality filled with a lot of color. Seeing a country slightly smaller than my own (Australia), and where I got to do a bit of business school (Penang), be systematically looted by the PM, his family and of course the criminal protagonist of this tale is enough to make your blood boil because the perpetrators appear to have gotten away with it all.

Crossing the Chasm

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Geoffrey A Moore (1991, 2012). Moore’s classic maps the perilous gap between early adopters and the mainstream market that kills most tech startups. He explains why enthusiasm from innovators doesn’t automatically translate to scale, and how positioning, messaging, and product focus must evolve to cross into the mass market. Still the definitive playbook for moving from promising idea to profitable company..

Review: An oldie but a goodie, the amazing thing about this book isn’t just its staying power – it is how it feels like it more relevant than at any point in the last 20 years. While many of the books here have shaped how I think about building Ascendius and growing the user-base of TeamScore, this book feels like it applies to a world where the audience is fragmented, unreachable and you have to earn the engagement from your ICP.

Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (1990). Introduces the concept of “flow,” a state of optimal experience where a person is fully immersed, focused, and energized by an activity..

Review: The closest book on this list to a religious experience, Mihaly’s book is dense, intense and it reads like the culmination of an incredible mind’s life’s work. I think I’m going to have to read it at least two more times – but I got so much out of the first read (I can still remember where I was standing and what I was looking at when I was listening to certain parts of it), I still recommend it without reservation.

If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies: Why Superhuman AI Would Kill Us All

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Eliezer Yudkowsky, Nate Soares (2024). Presents the argument that the development of superhuman artificial intelligence (AGI) poses an existential risk to humanity and is likely uncontrollable.

Review: A wild and super cerebral story which would be easy to put into the category of scaremongering hyperbole if it wasn’t for the credibility and pedigree of the authors. While understandably heavy on thought experiments – which are actually easy to read and understand, but way too elaborate to re-tell when you want to promote the book – this is a great read if you’re not already taking prescription meds for anxiety.

Invention: A Life of Learning Through Failure

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

By James Dyson (2021). James Dyson’s memoir about his life as an inventor and entrepreneur, emphasizing the critical importance of failure and persistence in the design process.

Review: An incredible story from one of the most determined and successful inventors of the last 30 years, Dyson’s autobiography contains both great insights and a lot of spicy opinions about the country he loves (and drives him mad). We had one of those knock-off Amway vacuums growing – reading how rotten they were made me wish we hadn’t. The UK is very lucky to have Dyson – definitely a diamond in the rough.

Man’s Search for Meaning

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Viktor E. Frankl (1946). A psychiatrist’s memoir of his time in Nazi concentration camps, where he developed “logotherapy,” a belief that the primary human drive is to find meaning.

Review: Understandably regarded as one of the most impactful books of the 20th century, I was surprised by the level of detail and the unvarnished nature of his insights on being in Nazi concentration camps. The psychology insights and lessons weren’t as extensive as I had anticipated given how impactful those insights have been over the years through other work, but this book is essential reading for any thinking person, especially with the echoes of the 1930s today.

Mindset

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Carol Dweck (2006, updated 2021). Introduces the concepts of the “fixed mindset” (believing abilities are static) and the “growth mindset” (believing abilities can be developed).

Review: A simple concept very well communicated, Dweck provides a great framework for use in business, education and especially as a parent. The examples – and self reflection – about why talented people with fixed mindsets get it wrong are exceptionally valuable.

Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Peter Attia MD, Bill Gifford (2023). A guide to longevity that focuses on proactive “Medicine 3.0,” aiming to extend healthspan by preventing chronic diseases rather than just treating them.

Review: Probably the most impactful book on my own personal health journey over the last year and a half, Attia’s clear, thoughtful and vulnerable book about increasing healthspan is mercifully short on preaching and unrealistic dictates, and instead focuses on the why of healthspan with very accessible and sensible tips on what you can do now.

Peak Human: What We Can Learn from History’s Greatest Civilizations

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Johan Norberg (2025). Argues that historical civilizations achieved greatness by embracing specific values like trust, openness to trade, and innovation.

Review: One of the best books I’ve read all year, Peak Human is witty, well researched and possibly the most nutrient-rich history of humanity that I’ve ever read. You could spend a few semesters studying history in University and only come out with half the insights and lessons from this incredibly written and frankly enjoyable book. The fact he points out that peak civilizations fall when they follow the current playbook of Western leaders is troubling but not at all surprising.

Problem Hunting: The Tech Startup Textbook

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Brian Long (2023). A textbook for tech founders on how to identify, validate, and solve meaningful problems before building a product.

Review: One of the most recommended books to my Startmate mentees, Brian outlines an excellent playbook for finding, validating and then going to market as an entrepreneur. This is also one of the few books I’ve re-read – it is that good.

Source Code: My Beginnings

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Bill Gates (2024). Bill Gates’s memoir detailing his early life, his formative experiences with computers, his intellectual development, and the founding of Microsoft.

Review: When the book is this long and it is just the first volume, you’d be right to worry it is going to be a slog. Fortunately, Bill’s style and content is anything but boring, and learning from someone who was right in the middle of the emergence of my industry in his own words is a really special treat.

Steve Jobs

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Walter Isaacson (2011). The definitive biography of the Apple co-founder, based on over 40 interviews with Jobs and 100+ with friends, family, and colleagues.

Review: Isaacson’s biography of one of the most important players in the technology industry is a tour de force, and it is amazing that at over 650 pages there is hardly a wasted word or unnecessary story. I didn’t take as many lessons away as an entrepreneur from Job’s story as I had expected, but the twists and turns of his journey and especially his later career triumph with NeXT, Pixar and the iPhone make for an incredible and highly entertaining story. And yes, I cried at the end, too.

The Basic Laws of Human Stupidity

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Carlo M. Cipolla, foreword by Nassim Nicholas Taleb (1976, this edition 2021). A satirical essay outlining five laws of stupidity, arguing that stupid people are a powerful and underestimated force in human affairs.

Review: Ironically not intended to be turned into a book, this impressive satirical essay is closer to the truth than I’d like to admit. The best book for understanding the current American political climate – for the first time (ever?), a coalition of the stupid, led by bandits, has managed to steal the future of the richest country on earth. A must read (which you’ll get through in 2-3 hours).

The Code Breaker: Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Walter Isaacson (2021). Details the life and work of Nobel laureate Jennifer Doudna and the scientific and ethical revolution of CRISPR gene-editing technology.

Review: A simple concept very well communicated, Dweck provides a great framework for use in business, education and especially as a parent. The examples – and self reflection – about why talented people with fixed mindsets get it wrong are exceptionally valuable.

The Fish That Ate the Whale: The Life and Times of America’s Banana King

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Rich Cohen (2012). Tells the story of Sam “the Banana Man” Zemurray, a complex and ruthless entrepreneur who built the United Fruit Company and influenced history.

Review: In this incredible story of a truly self-made man and an industry I’d never really thought about, Cohen does an incredible job illuminating the role of the fruit-barons in central to north American trade and the damage that they did to countries which in no small part remain impoverished and weak states to this day.

The Gambler: How Penniless Dropout Kirk Kerkorian Became the Greatest Deal Maker in Capitalist History

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

By William C. Rempel (2018). Chronicles the life of Kirk Kerkorian, a secretive and high-stakes deal-maker who built empires in aviation, casinos, and film.

Review: Recommended by one of my YPO Forum mates, Rempel’s biography of Kerkorian was an entertaining and enlightening tale about one of the most impressive entrepreneurs I’d never heard of. Finding myself in Vegas a month or so later and looking around at the town Kerkoiran more than anyone else “built” was also really special. If only his character in his professional life was maintained into his personal life, he could have done even so much more.

The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Walter Isaacson (2014). Chronicles the history of the digital revolution, focusing on the collaborative teams and individuals who created computers and the internet.

Review: Issacson’s next book after the runway success of his Jobs biography, this deeply researched historical piece should be essential reading for any tech entrepreneur. The people, their stories and the history of our industry that they created is entertaining and very very well written.

The Money Trap: Lost Illusions Inside the Tech Bubble

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Alok Sama (2024). A memoir from a tech investor about the excesses, hubris, and illusions of multiple tech investment bubbles and the lessons learned from being in the room.

Review: A fantastic story which weaved memoir and incredible first person stories from a wild time in capitalism with a great life lesson about doing what matters. What a debut book! I also hope to buy him a glass of satisfactory red wine on my next trip to NYC.

The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Morgan Housel (2020). Explores the strange ways people think about money, arguing that financial success is less about knowledge and more about behavior.

Review: This fairly short and easy read is probably the best book in its category that I’ve read. Examples like the story from being a valet in his younger years and noticing that everyone looking at a fancy car was never caring about the driver, and how people conflate acquiring things with earning respect and acceptance were a great antitode to the consumerist world we live in.

The SaaS Playbook: Build a Multimillion-Dollar Startup Without Venture Capital

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Rob Walling (2023). A guide for entrepreneurs on how to build a successful Software as a Service (SaaS) business through bootstrapping, without relying on venture capital.

Review: While Walling’s historical focus has been on the incrementalism of bootstrapping (his prior book is called “Start Small, Stay Small“), this compendium of tips on building a SaaS company was really on point regardless of whether you’re on the VC track or not. There’s almost nothing about this book I would change if I were writing it myself, which means now I’m not tempted to 😉

Thinking, Fast and Slow

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Daniel Kahneman (2011). This Nobel-prize winning psychologist summarizes his research on the two systems of thought: “System 1” (fast, intuitive) and “System 2” (slow, deliberate), and the cognitive biases that affect them.

Review: An incredible book from an incredible mind, Kahneman’s “Thinking, Fast and Slow” should be required reading in almost all professional and leadership domains. Unlike other authors on this list who made their case with anecdotes to support their thesis, Kahneman’s memoir or sorts is chock full of specific experiments and analytical data – so much so that it is one of the only books on this list I couldn’t get through in Audiobook form.

Trillion Dollar Coach: The Leadership Playbook of Silicon Valley’s Bill Campbell

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Eric Schmidt, Jonathan Rosenberg, Alan Eagle (2019). Shares the leadership principles of Bill Campbell, the legendary Silicon Valley executive coach who mentored Steve Jobs, Eric Schmidt, and others.

Review: Rosenberg, Schmidt and Eagle do a great job sharing the insights and experiences of the most influential Silicon Valley leader you’ve never heard of. The willingness to tell stories of Campbell’s career which don’t show him to be a saint, but instead a very real and deep leader, make it all the richer.

1929: Inside the Greatest Crash in Wall Street History – and How It Shattered a Nation

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Andrew Ross Sorkin (2025). An immersive narrative of the 1929 Wall Street collapse, threading high-flying finance, politics and human folly into the story of a financial empire’s unraveling.

Review: An excellent story expertly told, Sorkin provides a richness and depth to one of the most infamous years in American history – and critically, the many players involved. My only criticism was the lack of the wider lens into the ongoing causes of the Depression. Many are self-evident from the telling, but my only reason for not giving it 5 stars is it felt like it could have been a slam dunk with that extra color.

Bad Company: Private Equity and the Death of the American Dream

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Megan Greenwell (2024). An investigation into the private equity industry, arguing that its practices of leveraged buyouts are detrimental to workers and the economy.

Review: While it is clear from the title that this is going to be a negative piece about Private Equity in America, Greenwell takes a surprisingly balanced and hyperbole-free look at the industry, leaving the reader to form their own opinions. It reinforces my belief in how messed up it when the takers (using other people’s money no less) are making out like bandits at the expense of the builders, makers and creators who actually make the world a better place.

Building a StoryBrand

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Donald Miller (2017, reviewed and unavailable, now updated to Building a StoryBrand 2.0 in 2025). Presents the “SB7 Framework,” a 7-part storytelling method to help businesses clarify their message and connect with customers.

Review: Similar to April Dunford’s “Obviously Awesome” (below) but with a more structured 7-step framework for the way to use human’s natural way of learning – story telling – in how you connect with an audience.

Buy Then Build: How Acquisition Entrepreneurs Outsmart the Startup Game

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Walker Deibel (2019). A guide for “acquisition entrepreneurs,” advocating for the strategy of buying an existing, profitable business rather than starting from scratch.

Review: Walker’s book and insights were spot on, and while it is a bit unfortunate that so many smart people I know are now GP’ing “search funds” to make sure they get paid fees (rather than being true entrepreneurs), the playbook makes a lot of sense and I hope more true entrepreneurs follow his advice.

Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Daniel Pink (2009). Argues that true motivation comes from three internal factors: autonomy (self-direction), mastery (getting better), and purpose (serving something larger).

Review: Pink’s most prominent work does a great job of exploring how success in fields of non-routine work – which is almost all knowledge work today – comes down to having autonomy, mastery and purpose. His focus on managing by outcomes is also laudable, if often impractical since most non-routine work isn’t objectively measurable (in part because it isn’t routine).

Elon Musk

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Walter Isaacson (2023). A comprehensive biography detailing Musk’s life, risk-taking leadership style, and the inner workings of his companies (SpaceX, Tesla, etc.).

Review: Another great biography from Isaacson, his access to Musk and insights into the 21st century’s greatest entrepreneur before he went completely off the rails in 2024 lets the reader understand the path of a very influential which is incredibly valuable to have before the ultra-right Nazi-salute transition. Makes me want to go and read a biography of Howard Hughes now.

Find Your Why: A Practical Guide for Discovering Purpose for You and Your Team

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Simon Sinek, David Mead, Peter Docker (2017). A practical follow-up to “Start With Why,” offering step-by-step exercises for individuals and teams to discover their core purpose.

Review: A good practical playbook and follow up to Simon’s incredible “Start with Why” which I still vividly remember reading over a decade ago. I loved hearing how Simon, David and Peter have built a practice around Simon’s ideas. If you’ve read Start with Why, then you probably don’t need to read this, though, unless you’re trying to roll it out through a company.

Going Infinite: The Rise and Fall of a New Tycoon

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Michael Lewis (2023). Documents the meteoric rise and catastrophic collapse of Sam Bankman-Fried and his cryptocurrency exchange, FTX.

Review: Lewis has seen a lot, and you get the sense reading Going Infinite that he is just as confused and off-balance as the rest of us as the FTX story unfolds. The good fortune of his “fly on the wall” timing to be there through the apex of the FTX story was incredible, and the fact the book was written when the story wasn’t fully done made it even more interesting. SBF is a sympathetic is completely all over the shop character, and given FTX shareholders will make a profit (even after the scam of bankruptcy fees), as well as the fact he didn’t pay hitmen like Ulbricht, means I can see why the crypto-loving felon-in-chief will pardon him – unless CZ’s bribe for his recent pardon required keeping SBF in prison.

Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap…And Others Don’t

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Jim Collins (2001, 2005, 2010). Drawing on rigorous research, Collins identifies what separates merely good companies from truly great ones that sustain superior performance. With concepts like Level 5 Leadership, the Hedgehog Concept, and the Flywheel, he distills timeless truths about discipline, focus, and humility at scale. It’s less about charisma, more about consistency.

Review: Described by another author on this list as possibly the most in-depth and high quality studies of company performance ever undertaken, Collins’ classic has stood the test of time even if some of the great companies (Circuit City, Walgreens, Wells Fargo) subsequently lost their way.

Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Angela Duckworth (2016). Argues that a special blend of passion and perseverance (“grit”) is a more significant predictor of success than innate talent.

Review: Duckworth’s work, paired with the Growth Mindset approach of Carol Dweck, are essential reading for people who want to fulfil their potential and for the parents who want to help their kids do the same. I think Dweck’s view of being growth minded is more important than the sheer perseverance of grit, but if you’re growth minded but weak then you’re not going win, either.

Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Nir Eyal, Ryan Hoover (2014). This book presents the “Hook Model” — a four-step loop of Trigger → Action → Variable Reward → Investment — that explains how successful digital products become habits for users. It then applies this framework to show how product designers and marketers can increase user engagement, reduce reliance on expensive acquisition tactics, and build products that users return to almost automatically.

Review: A great book which brings together otherwise well explored psychology into a playbook that is essential reading for any entrepreneur or product leader. Unfortunately, most of our industry stopped reading before they got to the later chapter about “doing the right thing”, which seems to have prompted Eyal to write an antidote book to help sooth his conscience – but probably too late.

How to Make a Few Billion Dollars

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Brad Jacobs (2024). The memoir of serial entrepreneur Brad Jacobs, detailing his methods for building eight billion-dollar companies in different industries.

Review: Brad’s openness to sharing how we found valuable opportunities in what would be a private-equity roll-up playbook except that he actually ran these companies (instead of hiring a CEO and flipping them) was a great read with a lot of insights and unfortunately too many copy-cats trying to take short-cuts now.

In Praise of the Office: The Limits to Hybrid and Remote Work

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Peter Cappelli, Ranya Nehmeh (2025). Argues against the long-term viability of fully remote or hybrid work, highlighting the benefits of in-person office collaboration.

Review: Cappelli and Nehmeh do a great job of getting beyond the “preference” lens of remote vs office work (which for a lot of folks becomes a psuedo-religious attempt at justifying beliefs) and use data to help make the case for companies either getting back to their pre 2020 “normal” or investing the time and energy into making remote actually work..

Mindstuck: Mastering the Art of Changing Minds

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Michael McQueen (2023). Explores why people get “stuck” in their beliefs and provides strategies for effectively changing minds (including your own).

Review: Michael’s examples and stories help to frame a playbook for helping to change minds through constructive engagement and understanding. The old adage of “A mind changed against its will will be of the same opinion still” is as true as ever, and in our increasingly tribal and cultural conflicts, his book provides a great and care-led approach to helping to unstuck the minds of others – but most of all, your own. Also loved hearing my brother’s voice for 11 hours of self-narration!

Never Enough: From Barista to Billionaire

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Andrew Wilkinson (2024). The memoir of Andrew Wilkinson, detailing his journey from a small web design agency to building a $600 million company, and the personal cost of that ambition.

Review: A great and vulnerable story about the challenges of building a great business and then the insights into the benefits of investing in them instead. One of the few books on this list that I recommended to my wife – and that she then read and enjoyed!

Never Split the Difference

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Chris Voss (2016). Former FBI hostage negotiator Chris Voss brings field-tested psychological tactics to business and everyday life. His “tactical empathy” approach flips conventional wisdom, showing that great negotiators don’t compromise – they connect, listen, and influence through calibrated questions and emotional intelligence

Review: In instant fan favorite – who doesn’t love a book that starts like a lower-competency scene from Heat – Voss’ ability to bring real world experience to the concepts of really taking the time to get yourself into the shoes of the other person (Habit 5 from Covey) and then combining it with the insight that you make your counterparty come up with how you can give them what they want is brilliant. I just wish more salespeople didn’t just read it as a tactic for manipulation as opposed to a call for understanding and empathy to get deals done.

Obviously Awesome: How to Nail Product Positioning so Customers Get It, Buy It, Love It

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By April Dunford (2019). A practical guide to product positioning, teaching companies how to articulate their product’s value so that customers instantly understand it.

Review: Approachable and self-deprecating in a way only Canadian’s can be, April’s positioning book is tight and packed with really useful insights. A great and tighter compliment to Allyson’s Standout Startup.

Sales Pitch: How to Craft a Story to Stand Out and Win

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By April Dunford (2023). A guide on how to craft a compelling sales pitch by using storytelling techniques to stand out and connect with customers..

Review: A great and practical guide to selling with a focus on narrative as the driver to making a great connection with prospects. Builds and extends on her marketing book form 5 years earlier – I just hope her retention and client success book arrives before 2029!

Scarcity Brain: Fix Your Craving Mindset and Rewire Your Habits to Thrive with Enough

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Michael Easter (2023). Examines how modern scarcity cues hijack our brains and provides methods to rewire habits for contentment.

Review: Easter’s deep dive into the impact of our deep mental patterns of scarcity that drive caving is an entertaining read and the exposes of Vegas Slot/Poker machines from the perch of someone at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, is compelling. Unfortunately, you get the sense that he wanted the other anecdotes – especially the Iraqi minister and the tribe in the Amazonian jungle – to be more impressive than compelling, leading this book to slip into the Gladwell category (which is no doubt good for sales and being a keynote speaker).

Spam Nation

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Brian Krebs (2014). An investigative journalist’s deep dive into the shadow economy of organized cybercrime, focusing on the networks that produce spam and malware.

Review: One of the best bloggers on the security beat, Brian went all the way with this story and helped me understand more than anyone else the way the organized digital criminals can cause so much havoc. And that was before crypto made it possible to do real damage with ransomware and pig butchering! Amazing to think that this period in the late 2000s was an innocent age.

Standout Startup: The Founder’s Guide to Irresistible Marketing That Fuels Growth

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Allyson Letteri (2024). A marketing guide for early-stage founders on how to build a brand and marketing strategy that attracts customers and fuels growth.

Review: Allyson’s book provided a great framework with more span than many other books in the genre for having a great positioning, personality and ICP framework. Her website templates were also super helpful in doing my GTM planning work for TeamScore.

The Algebra of Wealth: A Simple Formula for Financial Security

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Scott Galloway (2024). Provides a formula for achieving financial security by focusing on stoicism, time management, and strategic (non-traditional) diversification.

Review: Having been a fan of Galloway from the first time I read his posts taking apart WeWork, and then more recently listening to him for a couple of hours a week on his numerous podcasts, I found this more measured and considered advice in book format to be an even better form of Prof G.

The Big Leap

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Gay Hendricks (2009). Introduces the concept of the “Upper Limit Problem,” an internal barrier that subconsciously sabotages people when they achieve success.

Review: Hendrick’s impactful and well regarded book takes a more scientific approach to making the psychological case to why we naturally have unnecessary mental limits because of our experiences. While it is considered part of the self-help category, I felt it was more a great piece to improve performance psychology vs help yourself out of a rut.

The Cold Start Problem: How to Start and Scale Network Effects

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Andrew Chen (2021). Analyzes how new networks and marketplaces successfully launch and scale by overcoming the initial challenge of needing users to attract more users.

Review: I was lucky enough to meet Andrew in one of his and Brian’s first Reforge classes in SF, and he continues to get the balance between thoughtful advice and practical experience right. While there’s always the temptation to take a victory lap, he made sure this book was practical and humble.

The Founders: The Story of Paypal and the Entrepreneurs Who Shaped Silicon Valley

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Jimmy Soni (2022). The detailed story of the “PayPal Mafia” (Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, etc.) and how their collaboration at PayPal shaped Silicon Valley.

Review: As a tech entrepreneur, I’ve known of the “PayPal Mafia” and their outsized impact on our industry for some time, but I’ve frankly never really been impressed with the PayPal product (I remember trying to build an integration with it 15 years ago and thinking it was a steaming pile of high fee garbage – and grateful that Stripe came along instead). Reading this story didn’t change my opinion of the product today, but I did learn a lot about the amazing things the founders did in what I now appreciate a lot more as a pioneering technology.

The Fred Factor: How Passion in Your Work and Life Can Turn the Ordinary into the Extraordinary

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Mark Sanborn (2004). Uses the story of a postal carrier named Fred to illustrate how passion and service can turn any job into an extraordinary opportunity.

Review: I was lucky to meet Mark a few weeks ago in Colorado, and bought his book on a whim after seeing him MC. I can see how this book and the story has been able to help Mark build an incredible speaking career, and the broad applicability of this simple but impactful story makes this light and easy read also easy to recommend.

The Outsiders: Eight Unconventional CEOs and Their Radically Rational Blueprint for Success

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By William N. Thorndike (2012). Profiles eight unconventional CEOs who achieved extraordinary long-term returns by mastering capital allocation and adopting a rational mindset.

Review: As a thesis, this isn’t the strongest book, but as what amounts to 8 mini biographies of incredibly successful CEOs, it is fantastic. So many lessons to learn, and Thorndike does a great job weaving them together in a way that provides both contrast and mutual reinforcement of the role of CEOs to focus not just on strategy but the need to wisely allocate the capital to make their strategy a success.

The Scout Mindset: Why Some People See Things Clearly and Others Don’t

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Julia Galef (2021). Contrasts the “soldier mindset” (defending beliefs) with the “scout mindset” (seeking truth) and argues for the superiority of the latter.

Review: A similar albeit subtly different message than Dweck’s 2006 Mindset, Galef makes a good case for keeping an open mind and remaining curious. Similiarly well timed to McQueen’s Mindstuck, this book could provide a good framework for folks stuck defending their worldview to learn from – although I fear the folks who most need to change their mentality are the least likely to do so.

What You Do Is Who You Are: How to Create Your Business Culture

⭐⭐⭐⭐

By Ben Horowitz (2019). Argues that a company’s culture is defined by its actions and virtues, not its stated values, drawing leadership lessons from history.

Review: A good, authentic book from Ben, although The Hard Thing about Hard Things was a hard act to follow!

Who

⭐⭐⭐⭐

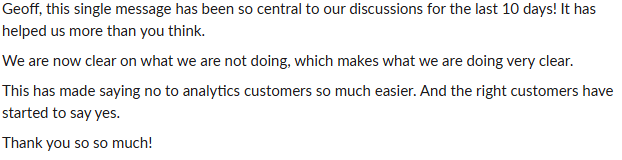

By Geoff Smart, Randy Street (2008). Smart’s Who reframes hiring as a repeatable business process rather than a gamble. With a focus on defining clear scorecards, structured interviews, and disciplined selection, it offers a practical playbook for consistently finding “A Players.” The core insight: the biggest mistake companies make isn’t what they do – it’s who they hire.

Review: I’ve been fortunate enough to get to know Geoff at a few events over the years, and he’s the real deal – obviously very smart (pardon the pun) but also genuine and interested in people and making a difference. Given my own track record of making disastrous hires and knowing first hand the millions it cost me, I loved Smart’s way of building the network of talent before you need them. Hiring is a massive gamble – he just helps you put the odds a little more in your favor, especially with his interview process.

Boomerang: Travels in the New Third World

⭐⭐⭐

By Michael Lewis (2011). A global tour of the post-2000s credit-boom hangover in Iceland, Greece, Ireland, Germany and the U.S., exploring how cheap money spilled across borders.

Review: The most caustic and opinionated of Lewis’ books, Boomerang tells many of the great stories behind the different folks who lost out from the 2008 financial crisis beyond the regular stories of American homeowners ending up underwater. He’s probably not welcome in a lot of countries as a result of this one – perhaps that’s why the book isn’t on Audible anymore?

Build: An Unorthodox Guide to Making Things Worth Making

⭐⭐⭐

By Tony Fadell (2022). Combines memoir and tactical playbook from the designer of the iPod and co-founder of the smart-home company Nest, showing how to build products, teams and businesses that matter.

Review: Tony’s book helps to unpack a process he followed to build some truly iconic products. The focus on the true goal/outcome as opposed to being insecure about how to look like you’re making progress was great.

Designing Your Life: How to Build a Well-Lived, Joyful Life⭐⭐⭐

By Bill Burnett, Dave Evans (2016). The original book that teaches how to use design thinking to create a more meaningful and fulfilling life, regardless of age or career stage.

Review: You can see why Bill and Dave run such a popular program at Stanford, with their practical advice on how to apply design thinking beyond your career lens.

Designing Your Work Life: How to Thrive and Change and Find Happiness at Work⭐⭐⭐

By Bill Burnett, Dave Evans (2020). Applies design thinking principles to help people find more meaning and happiness in their current jobs, without necessarily having to quit.

Review: A structured and thoughtful approach to reflecting on what you love to do, what you’re good at, and how to then apply design thinking to these insights to come up with a path that you can both enjoy and succeed at.

Gap Selling⭐⭐⭐

By Keenan (2018). A sales methodology focused on identifying the “gap” between the customer’s current state and their desired future state.

Review: It feels like there’s a million sales books out there, and the flaw with almost all of them is they could have made their case just as well in 2000 words, not 250+ pages. This book makes a great case – that sales isn’t about the seller, but all about the buyer – but it goes on longer than it needed to.

High Growth Handbook⭐⭐⭐

By Elad Gil (2018). A modern operator’s manual for founders who’ve found product-market fit and now face the chaos of hypergrowth. Drawing from conversations with top tech leaders, Gil breaks down scaling people, culture, operations, and strategy in a pragmatic, no-fluff format. It’s the book you wish you had once growth stops being theoretical.

Review: Elad’s compilation of so many great blog posts, this compendium of advice is rich in rounded insights for entrepreneurs. My main criticism is that, while an angel investor in so many of the companies that went on to become big, a lot of the advice comes from experiences as companies that were already pretty huge when he got there, making this less applicable for early stage operators.

How to F–k Up Your Startup⭐⭐⭐

By Kim Hvidkjaer (2021). Analyzes the common pitfalls and mistakes that lead to startup failure, offering practical advice on what not to do.

Review: A solid and fast moving book that is as filtered as the title, Hvidkjer does a good job pointing out the many landmines in the startup game. That said, I wouldn’t encourage my mentees to read it – they’re better off focusing on the prize, not ruminating on the failures.

Lives of the Stoics: The Art of Living from Zeno to Marcus Aurelius⭐⭐⭐

By Ryan Holiday, Stephen Hanselman (2020). A collection of mini-biographies of the major figures of Stoic philosophy, showing how they applied their principles in their lives.

Review: A great chronological journey through the world of the early stoic philosophers, the narrative was interesting and educational. The applicability is up to the reader – I found it mostly a story without happy endings.

Meditations⭐⭐⭐

By Marcus Aurelius, George Long, Duncan Steen (c 180 AD). The private journal of Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, outlining his personal reflections on Stoic philosophy, duty, and resilience.

Review: It is easy to see how this philosopher emperor casts such a long shadow as the last of the Five Good Emperors of the Roman Empire. As a book, it is pretty hard going and definitely not designed to be read cover to cover. It is also easy – and appreciated – to see how Ryan Holiday and others have made this great work much more applicable and digestible. If you want the good stuff, read The Obstacle Is The Way.

Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World⭐⭐⭐

By David Epstein (2019). Makes the case that generalists, not specialists, are better primed for success in complex and unpredictable fields.

Review: This was a very enjoyable read and appealed to my own bias to having a wide range of interests and knowledge. However, in the same way that a lot of Gladwell books are interesting, entertaining to read and “make sense”, this story leans a little too much on anecdotes to make its case, which makes it hard to steel-man.

Religion for Atheists: A Non-Believer’s Guide to the Uses of Religion⭐⭐⭐

By Alain de Botton (2012). Suggests that secular society can learn from and adapt the useful aspects of religion (like community, ritual, and moral guidance) without adopting its beliefs.

Review: A cerebral and respectful exploration of the drivers of religion and why an atheist should not throw the baby out with the bathwater. Unfortunately a bit too pompous in style to make it something I can heartily recommend.

Reset: How to Change What’s Not Working⭐⭐⭐

By Dan Heath (2025). Offers strategies to identify when something isn’t working in your life or career and provides a practical guide for making a significant change.

Review: An enjoyable read with lots of practical examples, this book is a useful update to his breakthrough book Switch from 15 years earlier.

The Art of Impossible: A Peak Performance Primer⭐⭐⭐

By Steven Kotler (2021). A high-performance primer that breaks down the neurobiology of “flow” and peak performance to help individuals achieve seemingly impossible goals.

Review: One of the first books I read in late 2024, this was a helpful gateway into a range of fields of performance psychology and excellence. Entertainingly written, Kotler provides a more anecdote driven exposition of the concepts championed by the “Father of Flow”, Csikszentmihalyi. My main criticism is that Kotler assumes the reader is already familiar with the sports-based feats he describes – while they sound impressive enough, if you don’t already know what he’s talking about, it is hard to really get on board with his anecdote-driven thesis.

The Phoenix Economy: Work, Life, and Money in the New Not Normal⭐⭐⭐

By Felix Salmon (2023). Analyzes the post-pandemic economic landscape, arguing that a “new normal” is emerging defined by inflation, labor dynamics, and new market forces.

Review: A prolific blogger and financial industry commentator, Salmon’s first book is well rewritten and dared to be insightful and predictive at a time when things were still very much in flux post pandemic. While not all insights have aged well – “new not normal” turned out not to be done of course – reading it 18 months after it was published was still interesting.

Hidden Potential: The Science of Achieving Greater Things⭐⭐

By Adam Grant (2023). Argues that success is less about innate talent and more about developing the “character skills” and systems to grow and achieve.

Review: Adam’s work is always a great read, but this one felt like a brand extension that didn’t need to be written.

Revenge of the Tipping Point: Overstories, Superspreaders, and the Rise of Social Engineering⭐⭐

By Malcolm Gladwell (2024). A revisit and re-examination of his original “Tipping Point” theory in the context of the modern social media and information age.

Review: As with all Gladwell books, this update to the breakout “The Tipping Point” is a fun read, written in an entertaining and accessible style with anecdotes that stick with you. Also like all of his work that I’ve read, the anecdotes help make a case but the case never really feels strong – emotionally compelling in the moment, but not as strong as many other pieces on this list.

The 38 Letters from J.D. Rockefeller to His Son: Perspectives, Ideology, and Wisdom⭐⭐

By J. D. Rockefeller (2006). A collection of personal letters from J.D. Rockefeller to his son, offering timeless advice on life, work, character, and generosity.

Review: Having previously read Ron Chernow’s Titan, the canonical biography of Rockefeller at almost 800 pages (over 35 hours), I didn’t get as much out of this book of letters as others may. The advice from an aging patriarch to his son trying to fill impossible shoes though are a precious gift and an opportunity to get advice first hand from one of the world’s most successful entrepreneurs.

University of Berkshire Hathaway⭐⭐

By Daniel Pecaut, Corey Wrenn (2017). Compiles 30 years of wisdom from Buffett and Munger’s insightful responses at the Berkshire Hathaway annual shareholders meetings.

Review: As the greatest investor of the last 100 years, Buffet (and Monger) are rightly people to learn from in business. Given their penchant for using their annual reports and their annual meetings as their main (in some years only) ways of making public statements, this summary of those annual meetings and the insights shared within was a good read, if not as nutritionally dense as some other Buffet content I’ve read.

Empire of Al⭐

By Karen Hao (2025). An investigative look into the power struggles, ethical dilemmas, and internal dynamics at OpenAI under Sam Altman’s leadership.

Review: A deeply reported piece in a fast changing and emerging industry from a writer closer to a lot of the players, but unfortunately it loses its punch/impact because the write goes all social justice warrior on how bad it is to pay folks in Africa to tag datasets (perhaps unemployment and hunger are more desirable?). Making this a story about colonialism loses the writer the credibility we need her to have at this time in history unfortunately.

Good Energy⭐

By Casey Means MD, Calley Means (2024). Argues that metabolic dysfunction is the root cause of many chronic diseases and offers a guide to improving metabolic health.

Review: Casey’s book is a strong and passionate exposition of a theory that the root of many health conditions is metabolic health. If she hadn’t then gone down the environmental zealot route with the unsubstantiated claims of everything organic being better for you, she’d have had a bigger impact. Unfortunately, the strong hippie-vibes means it will likely be mostly successful as preaching to the choir.

The Road to Character⭐

By David Brooks (2015). Contrasts “resume virtues” (skills for external success) with “eulogy virtues” (qualities of inner character) and argues for the importance of the latter.

Review: While by no means a regular reader of Brooks’ columns, I’ve often enjoyed his take through the NYT or PBS Newshour when I’ve read/watched them. Unfortunately, this book felt like more of a passion project than something that really needed to be written – if this is a domain you’re interested in, read the 7 Habits by Covey.

Your Next Five Moves: Master the Art of Business Strategy⭐

By Patrick Bet-David (2020). A guide to strategic thinking that teaches how to plan and anticipate outcomes five steps ahead in business and life.

Review: This was one of only two books on this list I couldn’t get through (along with Good Energy above). Perhaps it was style, or perhaps it was because the author is a “creator” who’s best known for creating the “Valuetainment” YouTube channel, but the 50 minutes I gave this title was time I’ll never get back.